"Your blood runs in my veins like a river of courage; I am the one who conquers time and turns the enemy into a brother. His strength burns within me, and we become one, pulsing under the sky like a flame that never goes out." — Antônio Torres, Meu Querido Canibal

"Eat to become stronger, eat to be the other and, at the same time, be more of yourself." This phrase could have come from the heart of a manifesto or from within a Tupinambá village. In fact, it echoes from deep within the past, from the earliest stories Brazil told itself. When the German Hans Staden, a prisoner of the Tupinambás in the 16th century, observed the rituals of cannibalism and trembled at the thought of being devoured, he likely could not understand what it meant. Staden left us a precious account: an image that would shock Europe, and centuries later would be reinterpreted not as an act of barbarism, but as the beginning of an idea—the first seed of what would eventually become the philosophy of Brazilian Cultural Anthropophagy.

The Tupinambás ate their enemies because they believed that by consuming the flesh, they took on the strength and virtues of the other. This, to them, was part of a pact with the world, a dialogue between bodies, a dance between the living and the dead. Eat to absorb, eat to transform. And wasn’t that, after all, what Brazil did throughout its history? We swallowed the world, consumed influences, devoured cultures, and transformed everything into something new, something with the taste of sun and earth.

Hans Staden wrote Duas Viagens ao Brasil (1557), and the French theologian Jean de Léry wrote Viagem à Terra do Brasil (1578). There, among astonishment and perplexity, we find the embryo of the idea of anthropophagy. For the Europeans, it was cannibalism; for the Tupinambás, it was ritual and culture. The Tupinambá cannibalism frightened and fascinated, but it also planted an idea: a society that devours the other not out of hatred or hunger, but to create a fusion, a force.

I begin with the German’s work because it’s the only one I’ve read. Staden, with his foreign and astonished gaze, observed Brazil for the first time. An adventurer adrift, with a history marked by struggles on both the Portuguese and French sides, captured and imprisoned by the Tupinambás, he witnessed up close what seemed to be "cannibal terror" and transformed this fascination into words. He spent 9 months in captivity, under the condition of fighting for that ethnicity to pay off his sentence, and he came very close to being devoured. His book, Duas Viagens ao Brasil (1557), records the pain and enchantment of a world where, among other things, the ritual of eating the other was not just savagery—it was a form of assimilation, a fusion of bodies and spirits. A spectacle that lasted days, with a well-structured script and impactful performances. 2

Centuries later, during the refinement of the 19th century, Eduardo Prado—an aristocrat, major coffee producer in São Paulo, thinker, lover of literature, and founder of the Brazilian Academy of Letters—acquired an original edition of Staden's book. It wasn’t just a collector’s whim. At a time when Brazil sought to define its face, this edition became a symbol of resistance against the European cultural empire, a way of shouting that we, too, were made of other roots, that Europe did not have the monopoly on the Brazilian soul. Prado, a member of the intellectual elite, heir to a coffee fortune, was eager to rediscover what was Brazilian in ancient times and, together with the Brazilian Academy of Letters (ABL), began recording this "Becoming-Brazil."

Forty years later, Paulo Prado, Eduardo’s grand-nephew, grew up with this ancestral memory, an echo of civilized savagery that would accompany him to the 1922 Modern Art Week, which he helped fund. Paulo Prado would become the patron of a generation that carried the spark of transformation and revolt. The result of an incessant search for genuinely Brazilian artistic production, the Week was an irreverent shout, a desire to dismantle conventions, devour, hungrily, European influences, and drink from the rich broth of local roots. It was here that Oswald de Andrade raised his Manifesto Antropófago and introduced us to the idea that devouring was, in fact, the secret to survival. Instead of accepting external influences peacefully, it was necessary to digest them, to transform them. Or, as Oswald would say, "I’m only interested in what is not mine. The law of man. The law of the anthropophagist." Perhaps Brazil had always been a promise of anthropophagy. We just needed to take the first step and embrace the hunger. Let it exist. No wonder "Look, our food is jumping" was an iconic phrase frequently spoken among the circles of those tropical modernist intellectuals.

"What is ours, we do not want to deny; we want to swallow and transform." That was the essence of the Manifesto. Oswald proposed that, instead of rejecting external influence, Brazil should devour it and transform it. That was the birth of Cultural Anthropophagy—a philosophy based on "devouring to create." Brazil, Oswald said, does not reject; it incorporates, mixes, dilutes, transforms. Indigenous anthropophagy became a metaphor for cultural creation. Being Brazilian, after all, meant having the ability to absorb the other and produce something entirely new.

In literature, Mário de Andrade wrote Macunaíma, the hero with no character who is also all characters. "Little health and a lot of saúva, these are Brazil’s ills," the hero would say in one of his tricks. In Tarsila do Amaral, anthropophagy was transformed into color and form with Abaporu—the figure with enormous feet and a small head, the man who eats people and is devoured by Brazil’s thousand possibilities. It was as if, suddenly, Brazilianness emerged as a new rhythm, a body that dances with history, devouring the past and the future at the same time.

The concept of anthropophagy was far from being a modernist joke or a provocation from Oswald. Swiss anthropologist Alfred Métraux, a keen observer of indigenous cultures, demonstrated how complex this practice was among native peoples. His studies showed that cannibalism was not a spectacle of barbarism, but a ritual of encounter and incorporation—an act of communion, of appropriating what the other has most vital. It was more than a physical act; it was a philosophy that Oswald and his modernist companions reinterpreted, transforming it into a manifesto for a cultural identity capable of absorbing the world without losing itself in it.

In the 1950s, this anthropophagy was reflected in music. Bossa Nova was a way of embracing American jazz and returning it with a tropical smoothness. When João Gilberto sings Chega de Saudade, he reveals the spirit of a nostalgic and delicate Brazil, a saudade that is both light and deep: “Go, my sadness, and tell her that without her it cannot be.” Bossa was a subtle form of anthropophagy, a melody that absorbed the foreign and transformed it into something else, something the world would hear with eyes closed, feeling the warmth of a distant beach.

Then, in the 1960s, Tropicália would elevate anthropophagy to the level of protest, to the political scream. Caetano Veloso, Gal Costa, Gilberto Gil, and other tropicalists devoured psychedelic rock, popular music, samba, and whatever else they could find, to create a sound that was deeply Brazilian and, at the same time, global. In Tropicália, Caetano describes a mythical and real Brazil, complex and contradictory: “I organize the movement / I guide the carnival.” Tropicália, with its explosive blend, took cultural anthropophagy to a new frontier: Brazil not only devoured the other, but also devoured itself, reinventing itself with each new rhythm, each new influence.

It is emblematic the account of Moraes Moreira about João Gilberto’s visit to the apartment of Novos Baianos when the group rented a penthouse in Ipanema, having recently emigrated from Bahia to Rio at the moment they were achieving national success. According to Moraes, beyond the shock of opening the door to that man, who in a brown suit and black tie looked more like an agent of the dictatorship in power at the time, João asked them to show him everything they knew, to display all the group’s musical virtuosity. In the end, he looked at them and said: “Everything is fine, but it lacks Brazil.”

At that moment, Novos Baianos were immersed in chords inspired by the new waves of international rock, with songs driven by lyrics that reflected the lightheartedness of Jovem Guarda and popular music of the time. However, the roots were missing — and João’s observation brought them back to the heart of that search.

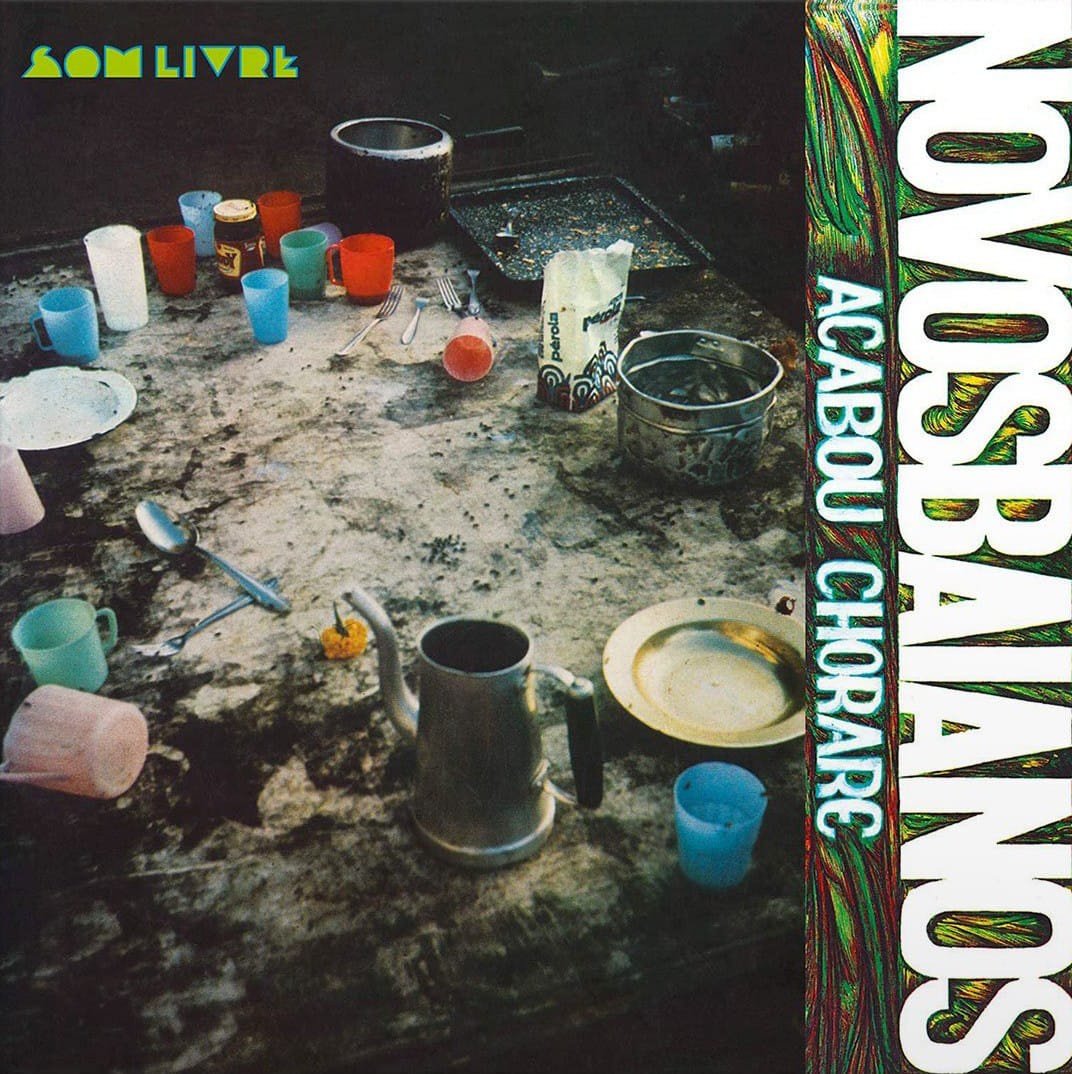

And that was it: drawing from samba and baião, incorporating themes and instruments from Brazilian popular culture, and blending it all with the beats and chords of the electric guitar, Novos Baianos created the iconic album Acabou Chorare. A milestone of Brazilian identity, it fused the global and the local, the new and the traditional, reinventing Brazil’s very own sonic identity.

These expressions of Brazilian music and art demonstrate that the anthropophagic metaphor is not merely about mixing but about constant creation and continuous reinvention. Each artistic movement, each cultural expression, represents a new kind of hunger. And this hunger is never satisfied because brasilidade is this eternal appetite for the other — the ability to transform what is external into something that defines and expands us.

This insatiable hunger didn’t stop. In the 1990s, Recife’s Manguebeat movement, led by Chico Science, brought the spirit of Tropicália to the Northeast. In A Cidade, Chico sings about a harsh reality, a devouring city: “A cidade se apresenta centro das ambições / Para mendigos ou ricos e outras armações” (“The city presents itself as the center of ambitions / For beggars or the wealthy and other schemes”). It was as if Brazil were devouring itself to better understand its own essence.

Not to mention the perfect blend of past and future crafted by the lyrics and arrangements of Baiana System, who, in the 2010s, updated the entire tradition of musical anthropophagy. This is the spirit of anthropophagy: a fearless embrace of absorption and transformation. It’s an act of courage that carries both the risk and the promise of being something genuine and inherently mixed.

Cultural Anthropophagy: The Key to Our Identity

The concept of Cultural Anthropophagy is not just a beautiful idea—it defines the essence of modern Brazilian culture. It is the secret key behind our ability to create a unique identity without rejecting external influences. This is why Brazil can produce a Tom Jobim and a Glauber Rocha, a Tarsila do Amaral and a Hélio Oiticica, a Tropicália and a Bossa Nova. In all these expressions, we see the capacity to devour the other and recreate it in an original way.

By embracing cultural anthropophagy, Brazilian culture becomes universal without losing its authenticity. We are mixed not only in blood but in soul, in aesthetics, in sound. Devouring the other is our way of existing. Transforming is our way of creating. Cultural anthropophagy has taught us to look at the world, to absorb everything it has to offer, and to turn it into a new way of being—a new art, a new music, a new poetry.

In the interweaving of voices, rhythms, and colors, Brazil is a body that pulses and expands, a skin that absorbs and reflects, unmaking and remaking itself, eternal and fleeting, dancing on the edge of the new and the ancestral. It is an identity built from pieces of the world, a living mosaic that draws strength not from borders but from embraces; not from what it rejects, but from what it devours, transforms, and returns. It is the jungle and the city, the drumbeat and the silence, the crack where the light enters, always making room for more stories, more sounds, more dreams.

This unique identity is strengthened not by everything it is not, but by everything it can be.

And it keeps on being—just like Gil's Rio de Janeiro.

1. Both can be found in PDF format and are easily accessible through a quick internet search. ↩︎

2. Hans Staden's account of the Tupinambás arrived in Europe like a bombshell in the second half of the 16th century. The publication of his book coincided with the flourishing of Renaissance and Humanist ideas that would redefine the understanding of humanity and society, such as Thomas More’s Utopia (1516), Niccolò Machiavelli’s The Prince (1532), and Montaigne’s Essays (1580). ↩︎

Foto: Flora Negri

Rafael Medrado é ator, produtor e pesquisador das Artes Performativas, com formação pela Escola Superior de Teatro e Cinema de Lisboa. Com uma trajetória que abrange o teatro, o cinema e a televisão, Rafael construiu uma percurso internacional, atuando no Brasil, em Portugal e em outros países.

Além de seu trabalho como artista, dedica-se à reflexão sobre temas como arte, cultura, filosofia, política e comportamento, compartilhando suas ideias em cursos, palestras e no blog Entre Outras Coisas.